After joining the army in 1948, Leslie Rutledge's father served in the Royal Engineers until he was demobbed in 1970. Leslie writes that during his father's twenty-two-year army career, 'he served in England three times, twice in Germany, once in Italy, once in Korea, twice in Hong Kong and once in Singapore, including a short tour of Borneo during the Malay–Indonesia conflict'. And, as Leslie notes, it was due to his father's military career that five of the eight Rutledge children who were born between 1950 and 1961 were born abroad, and that Leslie himself went to some ten different schools within a six-year period. The first part of Leslie's long and detailed story, which covers the years 1948 to 1953, follows. (See below for parts II to XI, and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood.)

'After he’d finished his apprenticeship as a shipwright at Hancock's Shipyard in Pembroke Dock [south-west Wales], Dad decided to become a soldier, like his father, who had served in the Royal Artillery for twenty-six years, and then for a further six years during the war in the Intelligence Corps as he was too old for active service. In February 1948, Dad accordingly enlisted at the Swansea army careers office and decided to join the corps of the Royal Engineers. His three basic trades, which he learned during training, were "Combat Engineer, Storeman-Tech and Carpenter". Hoping to be posted to some faraway, exotic country, he was rather disappointed when his first posting was confirmed as being back home in Wales, and he joined the 37 Army Engineer Regiment in Crickhowell, near Abergavenny, in March 1949.

When he was home on leave over the Christmas period in 1948, Dad and Mum were married at the registry office in Pembroke. Dad then went to Malvern Wells [in Worcestershire] to continue his training, and Mum stayed with her mother at Number 8 Kings Street, Pembroke Dock, as it was not usual for lower ranks to receive a quarter in those times.

POSTED TO TRIESTE

In January 1950, Dad was informed of his first overseas posting: he would be serving with BETFOR (British Element Trieste Forces) in the Free Territory of Trieste, Trieste [which is today in north-eastern Italy] being a piece of territory whose ownership had been contested between Italy and Yugoslavia since the latter's independence after World War I. In 1947, the United Nations had decided that the territory should be declared an independent state, which was then split into Zone A (Italy) and Zone B (Yugoslavia). Armed forces having been sent there as peacekeepers, Zone A was policed by the Americans and the British, and Zone B, by the Yugoslavs. As Dad could not be given a quarter, he travelled out on his own, and shortly before he left, Mum presented him with a daughter, Vicky. Dad then embarked on the four-day trip to Trieste via London, Harwich, Rotterdam, Germany and Austria. On his arrival, he joined 342 Army Troop, which belonged to the Royal Engineers' 66 Independent Field Squadron, and was stationed at the San Giovanni Barracks near the city centre.

It was over a year before Dad managed to arrange some private accommodation so that Mum could join him in Trieste, this being a small bedsit in a street called Via San Francesco d'Assisi, which was close to the city centre. Mum and Vicky were due to travel out together in May 1951 to join Dad in Trieste, but at the last moment Vicky caught the measles, so Mum travelled alone, which did not please Dad. He therefore arranged for a spot of home leave as quickly as possible, and in September 1951 they both travelled to Wales to bring Vicky back with them to Trieste.

Because my Mum and Dad were living in private accommodation amongst Italians, they quickly picked up the language, and later on in life would always speak Italian to each other if they didn't want us kids to know what they were talking about.

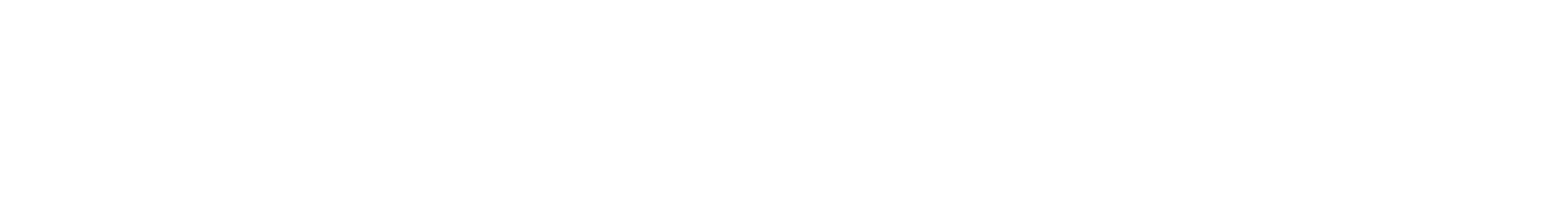

On 14 November 1951, the river Po broke its banks at a small town called Occhiobello due to heavy rainfall, which had swollen the river to overflowing. Two-thirds of Polesine ended up under water, 150,000 inhabitants had to be evacuated and 300 people died in Italy's worst flood disaster for over 500 years. The military was called in to assist in the humanitarian effort needed to rescue, feed and evacuate the civilian population, and the Royal Engineers' squadron at Trieste, including Dad, was sent to assist the Italians in their hour of need. The squadron was based at the town of Rovigo, the largest town in the area, where a makeshift camp of tents was set up as there was no other accommodation available. The men worked an eighteen-hour day, only stopping working to sleep. Shortly before Christmas, Mum heard a knock on the door and there stood Dad, totally exhausted, but glad to be home again.

In June 1952, a son, Chris, was born at BMH Trieste. And in August 1952, after having been married for almost four years, Dad and Mum were finally given a quarter in a block of flats in an area called Gretta, which was about 2 miles outside the town to the north-west. It was not quite ready, however, so they were moved into a hotel in the city centre for five weeks, and Vicky went to kindergarten. The quarter at Gretta was in quite a reasonable apartment block and was also on the ground floor, which any mother with two young kids would appreciate. Because you couldn't get a pram into a bus or taxi in those days, rations in assorted packs were brought out to the married quarters on a daily basis in a 15-cwt vehicle. The distance to the city centre also meant that Vicky could not go to kindergarten for the remainder of their time in Trieste.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART II

In the second part of his story (for Part I, see above; for parts III to XI, see below; and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood), Leslie Rutledge explains how his father, who was in the Royal Engineers, left both Trieste and the army in 1953 and returned with his wife and two young children to Wales, where Leslie was born. After rejoining the army in 1954, his father was posted to Korea, while his family remained behind in Perham Down, in Wiltshire. The two years that followed would encompass some traumatic events for the Rutledge family, as Leslie relates.

'After living in Trieste for more than three years, Dad was getting a bit restless. It was usual in the army to be posted after a three-year tour, so he applied for a posting, a request that the army turned down. He decided that the only way to get out of Trieste was to leave the army, and when his five-year contract ended shortly afterwards, he refused to sign on again. (By this time Mum was pregnant with yours truly, and if Dad had stayed in the army, I'd have been born in Italy instead of Wales.)

In May 1953, Dad left the army, and Mum and Dad, along with Vicky and Chris, travelled along the overland bus and train route from Trieste to the UK for the last time (I recall my mother telling me that travelling through the Rhine valley was the most pleasant train journey of her life). On arriving in the UK, my father had to travel to the Royal Engineers' headquarters in Barton Stacey [in Hampshire] to sign off, but as he still had three weeks' leave, he was then sent to a hotel in Blackpool to finish his time in the army. (My mother and the kids had gone straight to Blackpool from London.) In Blackpool, the family was housed in a room not big enough for two, let alone four; they were finding it difficult to understand why the army had sent them there in the first place. After three days, they decided to pack up and catch a train to Wales.

Right: My birthplace, the Riverside Hospital, Pembroke.

LIVING IN A NISSEN HUT AT PERHAM DOWN

After nearly nine months as a civilian, Dad decided that he'd had enough of civvy street and rejoined the army in February 1954. As he'd already served in the army and did not need do any basic training, he was sent straight to 32 Assault Engineer Regiment at Perham Down, near Tidworth, in the county of Wiltshire.

Left: Vicky and friend outside our quarter at Perham Down, Wiltshire.

In May 1955, Dad received the news that he was being sent to Korea as part of a United Nations' peacekeeping force. The war, which had been fought between 1951 and 1953, was now over, and although Korea had been split down the middle, along the 38th parallel, there was still a lot of tension between the communist-backed North and the pro-Western South. Dad was sent to Barton Stacey for his pre-Korea training and left in June 1955 to join the Royal Engineers' 55 Independent Field Squadron, thereafter spending nine months serving with the United Nations' peacekeeping force just outside Seoul. Whilst in Korea, he was allowed to go to Tokyo, in Japan, for two-week rest-and-recuperation periods.

Vicky started infants' school at the local school in Perham Down in September 1955. The problems with Stephen's heart were getting worse, and he had to be hospitalised. The doctors at Tidworth Military Hospital did not seem to be able to cure the problem, though, so at the beginning of September the decision was taken to send him to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London. On the morning of the planned transfer, my mother visited the hospital and was informed that Stephen had died shortly beforehand. Because his death came so unexpectedly, my father did not have time to get back from Korea for the funeral. Stephen was buried at the military cemetery at Tidworth four days later. The funeral was attended by my mother, her sister, the commanding officer, a sergeant major and a nurse from the hospital. I was too young to understand what was going on. Having just lost a child and being separated from her husband by half the world, my mother's grieving eventually landed her in hospital, and we three kids had to be fostered out. On coming out of hospital, she decided that she needed a complete break from Tidworth and went home to Wales for three weeks over Christmas.

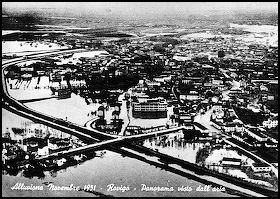

Above: Baby Stephen pictured at Tidworth Military Hospital (left); Mum at Stephen's grave at Tidworth Military Cemetery (right). In 2010, Leslie visited Stephen’s grave (‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘IN 2010, I VISITED MY BROTHER’S GRAVE AT TIDWORTH MILITARY CEMETERY’), erecting a headstone two years later (‘PERSONAL STORY: ‘MY MISSION TO ERECT A HEADSTONE ON MY BROTHER’S GRAVE’).

On returning to Tidworth, as if she hadn't had enough problems already, my mother discovered that the water tank and all the water pipes had frozen solid because the quarter had not been lived in for three weeks. The two allocated wood-fire stoves were lit up to try to defrost the water system, but early the next morning there was a loud bang and the water tank exploded, destroying part of the ceiling and leaving a big hole in the roof. Within minutes, the quarter was under 2 inches of water.

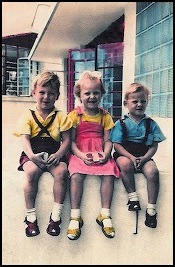

Right: Mum, Vicky, me and Chris in 1956, while living in Perham Down.

As sad as Stephen's death was, it helped to reunite the family as Dad was granted a compassionate posting to the Royal Engineers' 54 Field Squadron in Hong Kong, and arrangements were made for the family to be shipped out to the Far East to join him. The rest of the squadron left Korea soon afterwards for Christmas Island to build the camp for the nuclear-testing programme, so Dad was spared all that. He left Korea for Hong Kong in March 1956, but the next troopship heading for Hong Kong would not be sailing from England until mid-July, and would not reach Hong Kong until the end of August. My parents had now been married for nearly eight years, and had been separated for more than half of that time.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART III

The summer of 1956 saw the three-year-old Leslie Rutledge, his mother and two siblings all set to travel from England to Hong Kong, where they would be reunited with his father, who was in the Royal Engineers and who had been serving in Korea. In Part III of his story – for parts I and II, which span the family's time in Wales, Trieste and Perham Down, Wiltshire, see above, see below for parts IV to XI, and for his personal observations on an army childhood, click here – Leslie describes that unforgettable journey by troopship, their arrival in Hong Kong, and family life in Kowloon and the New Territories.

'In July 1956, we travelled up to Liverpool by train to board our troopship. The ship that we would be travelling on was called HMT [hired military transport] Empire Clyde, which had previously served as an ocean liner, the Cameronia, and would later carry emigrants to Australia. Although it was nearing the end of its life by the time we sailed on it, it was still quite posh, with a big, open staircase, large mirrors on the walls, mahogany panelling, plush bars and restaurants with waiter service – in fact, it seemed more of a cruise ship than a troopship. (As I was still quite young at the time, I can't remember much about the journey out to Hong Kong, but Mum said that it was an unbelievable experience for somebody like her, who came from a working-class background, to be given an "around-the-world-cruise" for free.) We set sail for Hong Kong on 17 July 1956, little realising that we were sailing into a diplomatic storm that would bring down the British government. Political tension had been building between Britain and Egypt for several years. Britain had completely withdrawn its forces from its former colony of Egypt, but had, along with America, promised Egypt funding for the building of the Aswan Dam, an offer that was later rescinded at short notice after Egypt recognised China in the United Nations. How would Egypt react? We would find out en route to Hong Kong.

We sailed down the Irish Sea and across the Bay of Biscay, stopping at Gibraltar for fuel and water and, after a few more days at sea crossing the Mediterranean, also at Malta. We then left Malta and headed for our next stop, Port Said [an Egyptian port at the northern end of the Suez Canal], after which we were scheduled to sail through the Suez Canal. On our arrival at Port Said on the evening of 25 July, we accordingly waited for north-bound ships to clear the canal, which allowed only one-way traffic. President Nasser of Egypt's reaction to the withdrawal of funds from Britain and America came the next day, on 26 July, when he decided to nationalise the Suez Canal, promising free passage to all ships of all nationalities during a two-hour speech in Alexandria. The Empire Clyde was held at Port Said for three days before being allowed passage through the canal, with no reason for the delay being given to the passengers. During that time, no passengers were allowed to leave the ship, also being ordered to have no contact with any of the Egyptian bumboats (small wooden boats selling goods to crews and passengers waiting to enter the canal). Later, all of the women and children were confined below decks after it was discovered that Egyptian men on the dockside were lifting up their smocks and revealing their bare buttocks in a show of defiance aimed at Britain. Mum claimed that ours was the first British ship to sail through the Suez Canal after it had been nationalised, but I haven't been able to confirm that. She also claims to have seen the Pyramids from the canal.

We eventually sailed on and made our next stop at Aden, where passengers were allowed to go ashore for the first time. Mum said that we were the first to return aboard as Aden seemed to be nothing but a fly-infested hole. From Aden, we crossed the Indian Ocean to Ceylon [now Sri Lanka], and the passengers were once again allowed onshore at Colombo to see how the locals lived. From Ceylon, we sailed down the Straits of Malacca and docked at Singapore, where the first troops left the ship, although the rest of the passengers were not allowed ashore. As soon as we had refuelled and taken on supplies and water, we left for Hong Kong, which we reached about five days later, after sailing across the South China Sea, arriving at the end of August after a six-week voyage.

REUNITED WITH DAD IN HONG KONG

Upon arriving in Hong Kong, we were transported to a hotel in downtown Kowloon, where Dad was waiting for us – it had been fourteen months since we'd last seen him. Once again, no quarter was available to us, and Dad had to find civilian accommodation, which took him about a week. (You'd have thought that the army would have treated its married soldiers a little better – by that time, Dad had been in the army for eight years, for most of that time married.) On our first night in the hotel, Mum decided to bathe us kids and was surprised to find the bath half-full of cold water. As it was so hot, she bathed us in that, drained the bath and put us to bed. Afterwards, she went to have a bath herself, but no water came out of the tap and she had to get one of the staff to come to the room and explain the situation. Looking rather bemused, the member of staff told my mother, "This Hong Kong, missy, water rationed". Apparently, she'd just bathed us in the only water that we would get until the next day (we soon learned to half-fill the baths every day at 6 pm because the water supply would then be turned off until the next morning). Luckily, the man managed to rustle up a couple of buckets of water so that Mum could have a quick wash and a cup of coffee. Welcome to Hong Kong!

After about a week, Dad managed to get us into some private accommodation in Mody Road, near Whitfield Barracks, just off Nathan Road. It was a block of flats seven stories high (which Mum claims was the tallest building in Hong Kong at the time), and we lived right at the top, with a beautiful view over the bay to Victoria on Hong Kong Island. Before we moved up to Sek Kong [now Shek Kong], another building was put up near to us, which was ten stories high. (Today, our first dwelling in Hong Kong is dwarfed by the new Hyatt Regency Hotel, which stands a stone's throw away and reaches 64 floors up into the sky.) As was usual practice in those days, there was not a stick of furniture in our new flat, and we were sent to a local Chinese shop in Nathan Road to hire some. In all, we hired out a kitchen, a set of living-room furniture and four beds, and it only cost us $HK80 a week, which was about £1 at the time.

Shortly after moving in, we were allocated our first amah (house servant), which every married couple was given in the Far East. Her name was Chan, and she took an immediate liking to me, probably because of my snow-white hair, and called me "China Boy". Like a typical Chinese mother, she carried me on her back everywhere she went in one of those cloth scarves. Unlike some of the amahs we had later, she was extremely hard-working and family-friendly, and soon became almost part of the family. Vicky started school at Whitfield Barracks Junior School, which was just around the corner from us, while Dad's camp was up in the New Territories, at a place called Tai Lam Chung, which had the nickname the "Twenty-five Mile Camp", probably because it was 25 miles outside Kowloon, where most of the married men lived. One day in November 1956, whilst I was pushing Chris on a swing in the local park, the wooden seat of the swing hit me in the mouth and knocked out my two front teeth; luckily they were my milk teeth, but my second teeth were pushed right up into my gums and it took nearly four years for them to grow out. Until they did, my Dad always sat me on his lap and sang to me the old Nat King Cole song, "All I Want for Christmas are My Two Front Teeth".

In June 1957, we moved up to Sek Kong Village in the New Territories, and were given a quarter at number 41. Sek Kong was very laid-back and rural compared to life in Kowloon, which seemed to be lived at 100 miles an hour. Vicky started school at Sek Kong Junior School, which was on the main Route Twisk road leading from Kowloon to the Chinese border. At the beginning of August, Dad took Vicky, Chris and me to Victoria, on Hong Kong Island, via the Star Ferry to see our new baby brother, George, who had just been born at the British military hospital on Bowen Road. Shortly after that, Chris joined Vicky at Sek Kong Junior School, whilst I, aged four, started school at Sek Kong Nursery School. As I recall, I quite enjoyed going to school as we spent most of the time playing anyway. I was also about four when I learned to swim: Mum and Dad would quite often take us up to the pool at the Signals barracks near Yuen Long, where Mum would give us swimming lessons. A couple of times, she just threw us into the pool and said "Get on with it – swim or drown". By the time we left Hong Kong in 1958, we were all good swimmers.

Below: A typical army quarter in Sek Kong Village.

While we lived in Hong Kong, I became well known by everyone for my running-away-from-home escapades. It wasn't that I didn’t love my parents, just that even at that early age, I discovered that I possessed a spirit of adventure. Most kids wanted to play in the sandpit, but I wanted to see the world. Having decided at quite an early age that I wanted to visit every country in the world, I'd quite often just get up and wander off, which used to drive my parents mad, no doubt. Dad had to come and collect me from the guardroom at the Chinese border on more than one occasion, and putting up with all the leg-pulling from the guards must have been rather embarrassing.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART IV

In previous instalments of his story, Leslie Rutledge recounted how after his father joined the Royal Engineers in 1948, his ever-growing family followed him to Trieste (see Part I, above), to Wales and Wiltshire (see Part II, above) and then to Hong Kong (see Part III, above). In this, the fourth part of his account, Leslie recalls sailing back to the UK in 1958 before boarding a train for the family's new home in Paderborn, (West) Germany. (For parts V to XI, see below, and for his personal observations on an army childhood, click here.)

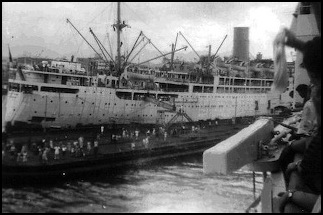

'In 1958, Dad received the news that 54 Field Squadron RE [Royal Engineers] was to be posted back to the UK en masse and that he was then bound for Barker Barracks in Paderborn, Germany. This time, Dad sailed with us, and we left Hong Kong harbour in May 1958 on the troopship HMT Oxfordshire, homeward-bound for Liverpool. Unlike the Empire Clyde, the Oxfordshire had been purpose-built for transporting troops around the world and was almost brand new, having made her maiden voyage coming out to Hong Kong only a year earlier. There were hundreds of people on the quayside as the ship pulled away, and streamers were thrown off the boat, as was normal practice during the 1950s when embarking on a long sea voyage.

THE SEA VOYAGE FROM HONG KONG TO ENGLAND

The journey back to England took about five weeks, and the ship stopped at Singapore, Colombo, Aden, Suez, Port Said, Malta and Gibraltar. Soldiers – even married ones – were not allowed anywhere near the family cabins and slept in large cabins full of hammocks on the lower decks. Colombo, in Ceylon [now Sri Lanka], was the only place where I left the ship, Dad playing babysitter to George on the ship whilst Mum took Vicky, Chris and me to Colombo Zoo for the day. I remember having a ride on an elephant's back and being quite scared when we were going through the snake compound because at that age the pythons seemed massive. I remember a lot more about the return journey than the outbound one. On one occasion whilst sailing across the Indian Ocean, we were accompanied by a school of dolphins, and a few days after that, a shoal of flying fish suddenly appeared from nowhere, which was quite a funny sight as they'd jump up out of the water, flap their wings and then, after about 50 metres, fall back into the water. One day on board we held a school sports day, which was really good fun. The winners of each event were given presents, but I never won a sausage, as I recall. Emergency drill was carried out on the ship quite regularly, and whenever the sirens went off we had to run to our muster stations and put on our life jackets. Of course, children of school age had to attend classes, but being only four years old, I was not quite of school age, so I spent all day playing around the ship. When we reached Aden, the harbour was full of Arab dhows and the buoys were made out of old oil drums, which were all painted a sickly bright-green colour. On our return voyage we sailed through Egypt and the Suez Canal with

Right: The Oxfordshire making a refuelling stop at Aden in 1958.

When we arrived in Liverpool, our family was again put into accommodation in a hotel in Blackpool, where we should have stayed for three weeks. Dad went down to Pembroke Dock to stay with his parents, and after a week in Blackpool and a lot of messing about from the landlady, Mum grabbed us kids and got a train back to Pembroke Dock, where her mother greeted her with open arms. We lived there for about two weeks until we moved to Germany. It was the first time that I recall seeing my grandfather; sadly, it would also be the last. Whilst in Pembroke Dock, I went to my first civilian school, along with Vicky and Chris, attending Albion Square Infants School.

FAMILY LIFE IN PADERBORN

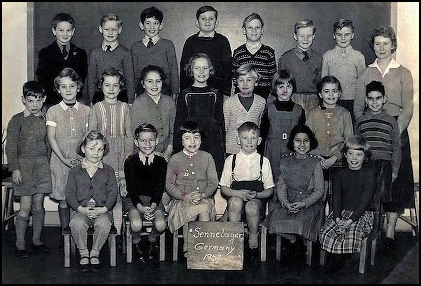

We travelled by train to Germany in July 1958. We followed the same procedure that my parents had done many times before when going to Trieste during the early 1950s, only this time we caught a troop train going to Germany at Rotterdam. On arrival in Paderborn, we were picked up by transport and transferred to Barker Barracks, where we moved into one of the accommodation blocks inside the camp that had been turned into family quarters. Dad then joined 1 Field Squadron RE, and after the school summer holidays, Vicky, Chris and I started junior school at Sennelager Junior School, which was up in Normandy Barracks. In Germany, the army had its own currency called BAFVs (British Armed Forces Vouchers), these special vouchers all resembling bank notes (even the one for thrupence); BAFVs could only be spent in British or American institutions. Each serving soldier was also issued with a certain amount of the local currency for private purchases outside the military zones.

Above: Vicky appears front left in a class picture taken in 1958 at her primary school in Sennelager.

One day in February 1959, we nearly had our second death in the family when Mum sent Chris and me to the German bakery down the road to get some bread. On the way home, we decided to cross the main road into Paderborn and re-enter the camp through a side entrance, which was much quicker than going all the way up to the main gate and back. I saw a gap in the traffic and ran hell for leather across the road, with Chris running after me. Then all I heard was a screeching of brakes and a dull thud as he was run over by a car, which just missed me – I had misjudged the speed of the car completely. When I turned around, Chris was lying in a still heap about 50 yards down the road. As I rushed over to him, I could hear my mother screaming in the background, having witnessed the whole incident from the block window. Too shocked to take it all in, I stood in the middle of the road looking down at Chris. He looked as though he was sleeping, but was covered in blood and sick. I knew that it was my fault that this had happened. Somebody dragged me away from the scene as my mother arrived, crying her eyes out. Soon a German ambulance arrived and Chris was rushed to the German hospital in downtown Paderborn. He should have been killed outright as the car was travelling at over 70 kph; as it was, the German doctors didn't expect him to live for more than twenty-four hours. A local German nun came in and prayed for him as he lay there in a coma. Yet for some miraculous reason he clung on to life, and as each day passed, he gave the doctors more hope of his recovery.

Below: Chris (on the right) recovering in hospital after his accident in 1959.

In June 1959, Mum and Dad both fell ill and were admitted to hospital at the same time, and we four kids were fostered out to live with other families for the duration of their stay in hospital. I stayed with a family called the Fishers – I think Mr Fisher was an officer – who treated me like a little god whilst I stayed there and let me stay up longer than I was allowed to at home, which pleased me. I was a bit sad when I had to leave, but happy to have my parents back home again. Mum and Dad having bought a large wooden radio–gramophone set, which looked lovely, the wireless now seemed to be on all the time, and I remember listening to some of the hits of the era, like Rosemary Clooney's "Where will the Dimple be?" and "Lipstick on your Collar", by Connie Francis. I can't remember being much interested in the new rock-'n'-roll-style music like Bill Haley's "Rock around the Clock", which had come out in the mid-1950s. That would come later.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART V

Leslie Rutledge's parents were married in 1948, the same year in which his father joined the Royal Engineers. In previous parts of his story (see above), Leslie traced both his family's expansion and their lives in Trieste (Part I), Wiltshire (Part II), Hong Kong (Part III) and Paderborn, in (West) Germany (Part IV). As he now recounts, the next chapter of the Rutledges' tale would see them move from Paderborn to nearby Sennelager – and add three more children to the family fold – before spending a short period living in a hostel in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, prior to flying to Hong Kong. (See below for parts VI to XI, and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood.)

'In June 1959, Dad had an inter-regimental posting to 44 Field Park Squadron RE [Royal Engineers] and the family moved to a new quarter in Ringstraße, near Normandy Barracks in Sennelager. The new house had its own garden, which pleased Dad as he liked to do a bit of gardening. Just across the road was a play area, including a sandpit and swings. In 1960, Dad got a car from somewhere. I don't think he even had a driving licence, but believe that he wanted to take driving lessons and drive us around a bit. He never bothered, though, and the car stayed parked outside the house for the rest of our stay in Sennelager. (It was the only time that we owned a car whilst he was in the army.)

Above: Our quarter in Ringstraße, Sennelager (photograph taken in 2001).

FAMILY GAINS AND LOSSES

I started going to Sunday school quite regularly, which I put down to my love of history and geography, my favourite subjects at school. Every week, a story was read to us out of the Bible by the padre, which fascinated me. At the end of each lesson, we were given big, colourful stamps, which we used to stick into a storybook album. In July 1960, Mum presented Dad with his second daughter at the medical reception station [MRS] in Sennelager. Nic soon became Dad's little darling. And by the end of 1960, Mum again had a pot belly. (Later, when asked why he had so many kids, Dad would always jokingly say, "Well, we didn't have telly in those days".)

In April 1961, Dad came home from work and told us that our granddad, his father, had died suddenly after a short illness. It was a bit difficult for us to take in, partly because we were so young and partly because we'd only ever seen Granddad a couple of times. I remember feeling quite sad, but not crying. Dad went back to Wales for the funeral on his own. One of the saddest things about army life was growing up without extended family, like grandparents, uncles and cousins. Both of my grandmothers died shortly after we'd left the army, and I never met my second grandfather.

During the time that we lived in Paderborn and Sennelager, we went up to the Royal Engineers' open day every year in the summer holidays. This was held at Hamelin [or Hameln] on the river Weser. Members of the corps would be bussed in from all the major garrisons – like Osnabrück, Nienburg, Hohne and Iserlohn – where they were serving. All sorts of gadgets would be on show, and we were driven around in tanks and other military vehicles. As I recall, most of the dads spent most of their time in the beer tent, meeting old friends and chatting about days gone by.

Above: Chris pictured in class in Sennelager in 1961 (left); a school portrait of me in 1961 (right).

In May 1961, Vicky sat her Eleven Plus and passed, so after the school summer holidays she started senior school at King's School (a grammar school), in Gütersloh, whilst George started nursery school in Sennelager. At the end of August 1961, Mum had twin girls at the MRS in Sennelager. No one had suspected for a minute that she was carrying two babies as in those days there was no such thing as a scan, so we were all pleasantly surprised by the news. It turned out that Teresa (the first-born twin) and Tracy (who turned out to be the last-born baby of the family) were not identical. At Christmas, I got a Märklin train set, which is what I'd asked for. But then Dad spent most of the time playing with it, while Chris and I watched, somewhat "piffed off" – sometimes I wondered whether he'd bought it for himself.

THREE MONTHS IN ESSEX

We had now been living in Germany for more than three years, and our next posting was due. Dad was accordingly posted to Singapore, but because his new regiment was still in Hong Kong and would not move to Singapore until September 1962, the army decided to send us to Hong Kong first for six months. So in February 1962, Dad left for Hong Kong and the rest of the family flew back to England from Gütersloh in an RAF Hercules [transport aircraft]. It was the first time that I'd flown, so I was quite excited about the whole thing. I remember that it was a four-propeller plane and very noisy, and that we sat in canvas bucket seats – it was not exactly equipped for passenger travel. We landed at Gatwick and were bussed up to Victoria, in London, travelling from there to Westcliff-on-Sea, near Southend in Essex.

The hostel where we were accommodated was large, but a bit of a dump that had obviously seen better days. The place was also freezing, being without central heating, and we had only a couple of electric fires to keep us warm (when we arrived, they were switched off). We lived right on the seafront and spend a lot of our spare time playing on the beach. It was too cold at that time of the year to swim in the sea, though.

Vicky attended Westcliff High School for Girls, and Chris and I went to Westcliff Junior School, which involved quite a long walk of about 4 miles there and back. I felt a bit left out as I was new and all the other kids knew each other. As I would only be there for a couple of months, I thought to myself, "What is the point of making any friends?" There were other army families back at the hostel, so we hung about with them most of the time. Not far from where we lived was Southend Pier (famously known as the longest pier in the world, at nearly 1½ miles long). Part of it had been destroyed by fire in 1959, and the restoration work had just finished when we arrived, so everything was like new. We spent a lot of our free time at the amusement arcades on or around the pier.

One day, Mum's mother, Gran Pearce, turned up and stayed with us for about a week. We had a family photo taken, and I think that it was the first photo taken with all of us seven kids in it (Dad was, of course, missing as he'd already left for Hong Kong). It was the first time that I'd seen her since 1958, and I would not see her again until 1970, just before we left the army. One night, my mother took Vicky, Chris and me to the cinema to see a film called The Road To Hong Kong, starring Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, which seemed appropriate since we were just about to go there. It was the first time, as far as I can recall, that we had gone to the cinema at night, and we ended up going to bed much later than usual.

"Inoculation time" was something that all service families had to go through before going to the Far East. Being used as a pincushion used to drive me mad because I was terrified of needles – I still am – and the inoculation process usually required quite a few different jabs for all sorts of exotic illnesses. Most of the time, I tried to hide under the table, or somewhere else, when we went to the doctor's to have our jabs, hoping that he'd forget me, but he never did, and I usually had to be dragged into the room and held down with force whilst he did his business. I hate injections even today, and never go near the dentist unless it’s unavoidable.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART VI

Between 1948 and 1962, the growing Rutledge family lived in Trieste, Wiltshire, Hong Kong), Paderborn, in (West) Germany, and Sennelager, also in Germany (see parts I to V of Leslie Rutledge's story, above; see below for parts VII to XI; and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood). And as a result of their Royal Engineer father's new posting, the Rutledge children's next home would again be in typhoon-prone Hong Kong, as Leslie now relates.

'In May 1962, the family flew out to Hong Kong from Stansted Airport, once again in a noisy, four-propeller machine, but this time a civilian, BOAC [British Overseas Airways Corporation] plane more suited to passenger travel. At the airport, Chris and I were running about like lunatics – as usual – when Chris tripped over something and landed on his mouth. One of his front teeth was chipped off and there was blood everywhere. The airport doctor had to put stitches in the wound, but allowed us to carry on with the journey. The flight out to Hong Kong took nearly two days, and we stopped at Istanbul, in Turkey, and Bombay, in India, to refuel and stretch our legs. Flying over the Himalayas during the last part of the flight was probably one of the highlights of my life. Hong Kong is situated in a bay surrounded by mountains; on one side is the mainland, with the city of Kowloon, and opposite is Hong Kong Island, with the city of Victoria. The airport, which was called Kai Tak, was built with the runway jutting out into the sea, making landing there quite difficult (more than one plane had misjudged the landing or had taken off and had ended up in the sea).

SIX WEEKS IN KOWLOON

On arrival, we were transported to our new apartment in Nga Tsin Wai Road in the middle of Kowloon city, which was in a block of flats owned by a Chinese man who rented them out to the army. Although there were other army families in the block, Chinese locals inhabited the surrounding area. One thing I noticed on the way to our new abode was how much Kowloon had shot up into the sky since we left in 1958. There were far fewer skyscrapers then, and they were not so tall, whereas now every block seemed to be a skyscraper twenty floors high. When we arrived at the flat, I remember Mum going into the kitchen to check it out; when she opened the cupboard under the sink, hundreds of cockroaches ran out all over the kitchen floor, which made her jump, and we all panicked a bit, too. The first thing she bought was insect repellent.

I remember having an amah in this flat, although Mum sacked her after only two weeks and had her replaced because she was constantly absent from duty, and all amahs were supposed to live in. Vicky started grammar school at St George's School in Norfolk Road, while Chris and I went to the junior school in Whitfield Barracks, which was just down the road from the Star Ferry (my teacher was a pain in the neck, as I recall). We'd often go up to the Gun Club in Kowloon, which was a military recreation centre that included a swimming pool. We stayed at this flat in Kowloon for only six weeks. During that time, I would frequently sit outside with the Chinese boy of my own age who lived next door, watching him writing, using a paintbrush and painting the Chinese characters from the bottom right-hand corner to the top left-hand corner.

One day Nicola, Dad's little darling, disappeared. The whole family searched the streets around the flat, but there was no sign of her. When Dad came home, he was devastated, and the military and local police were informed. Later that night, we received a phone call from the Royal Hong Kong Police Force saying that Nicola had been found wandering around Kowloon city centre and asking us to pick her up from the police station. When we did so, the Chinese policemen were having a laugh about it, and Dad was both quite embarrassed and relieved.

TWO MONTHS IN SEK KONG

In July 1962, Dad came home with the news that we were moving into a quarter up in Sek Kong [or Shek Kong], where we'd lived in 1958. The apparent reason for the move was that we could only get a quarter in Singapore if we had one in Hong Kong before we left. So we once again packed up and moved, this time to house number 44 in Sek Kong Village, then remaining in the New Territories for the final two months of our stay in Hong Kong. Here, we had a new amah called Kim, a young and very attractive Chinese girl. The house was only a stone's throw from the house in which we had lived during our last visit here.

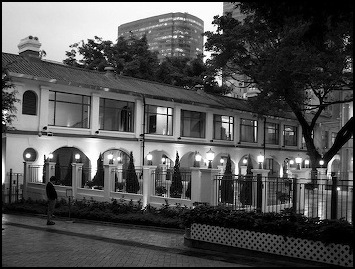

Left: The former premises of Sek Kong School, pictured in 2006.

One of our favourite pastimes in Sek Kong was surfing the monsoon drains, which was great fun, but extremely dangerous. The Sek Kong quarters were built on the lower slopes of Tai Mo Shan, which we called "Mount Pimple", and which was Hong Kong's highest mountain. When the monsoon came, the rains belted down, so 6-foot-deep drains ran through the village to help clear the water away. Chris and I, and also some of the other kids, would go to the highest point in the village and, using anything handy, would then surf down the drains to the bottom of the village. Chris and I also joined the Cubs at Sek Kong – it was the only place where we lived where we were in the Cub or Boy Scouts – but as we were only there for a couple of months, we didn't even have time to get uniforms on to which we could sew our proficiency badges.

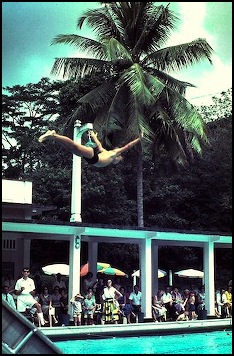

One day, whilst swimming in the pool at Sek Kong Village, I dived headfirst into the pool, not realising how shallow it was at that point, and banged my head on the bottom. When I stood up, everything was red, and I felt completely dizzy. Someone who had seen the mess that I was in jumped in, dragged me out and laid me out on a bench, where it seemed that everyone there then stood around me, gawking. Mum turned up and told me that the skin on my forehead was split from one side to the other. Shortly after that, an ambulance arrived and took me to the medical centre, where I was given several injections and about ten stitches in my forehead. The pool had to be emptied and refilled because of hygiene-related safety regulations.

HIT BY TYPHOON WANDA

Just before we left for Singapore, we had to go through one of the most terrifying ordeals of our lives, when, on 1 September 1962, Hong Kong was struck by Typhoon Wanda. Typhoons are common in this part of the world, but on our first visit to Hong Kong, we had encountered only tropical storms. This, too, had seemed to be no more than a tropical storm when it rounded the Philippines and headed towards Hong Kong, but by the time it had crossed the Luzon Strait, it had turned into a full-blown typhoon. To make matters worse, Hong Kong was due to have a high tide at about the same time as the typhoon was due to make landfall, and the course of the typhoon would go straight across the centre of the colony. All of the fathers were sent home for the duration of the typhoon, and all families were ordered to stay indoors until it had passed by, and to keep all the doors and windows shut (luckily, our house had shutters on the windows).

The typhoon struck land at about 6 o'clock in the morning and lasted for about twelve hours, with the eye of the storm passing over us at around midday. The noise of the wind and rain pounding on our roof was like thunder, with 12 inches of rain falling in those twelve hours. At Tolo Harbour, the tide rose more than 20 feet above normal high-tide height, causing massive flooding and damage – hundreds of boats and houses were totally destroyed, and hundreds of acres of crop land were destroyed by sea water. When the eye of the storm passed over us at about noon, everything fell absolutely silent – almost like a cemetery at midnight, with no birds chirping and no dogs barking – you could have heard a pin drop. After about a forty-five-minute lull, the noise that made it sound as though the world was ending resumed, and lasted for another six hours.

By the morning of 2 September, the typhoon had passed, so we went outside and had a look around the other quarters. We lived near the bottom of the valley, so the damage wasn't too bad, except for a few broken windows and several large branches lying around that had been ripped off nearby trees. Debris and stones were lying everywhere, and the rear of our house was embedded with stones and holes where more stones had hit the wall – it looked as though the house had been machine-gunned. A lot of the quarters near the top of the hill were badly damaged, though, with many of them being roofless. The ones that had lost their roofs were also badly damaged inside, and most of their contents had disappeared (gone with the wind, so to say). Typhoon Wanda turned out to be the strongest typhoon ever to hit Hong Kong, breaking previous records of wind speed (133 kph) and minimum instantaneous pressure (953 mb). A typhoon in 1937 had caused more deaths (11,000, to only 130 this time), but the material damage was far higher. All in all, we felt lucky to have survived it with no loss to limb or property, as our crates were all packed up in the house, ready for the move to Singapore.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART VII

As Leslie Rutledge revealed in Part VI of his tale of army childhood (see above), the year 1962 had already been an eventful one for his family when, in the autumn, they all flew to Singapore so that his father, who was serving with the Royal Engineers, could take up his new posting there. Although the Rutledge family had already experienced life in Trieste (see Part I, above), Wiltshire (Part II, above), Hong Kong (Part III, above), Paderborn, in (West) Germany (Part IV, above), Sennelager, also in Germany (Part V, above), and Hong Kong (Part VI), Singapore was new to them. Leslie now continues his story (see below for parts VIII to XI, and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood).

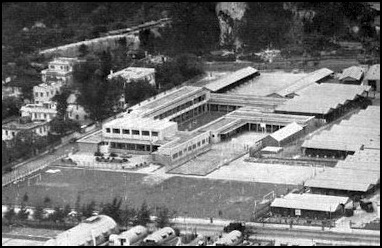

'We left Hong Kong and flew to Singapore a couple of weeks after Typhoon Wanda had struck, during which the Royal Engineers had spent a lot of time cleaning the place up. I remember that while I was sitting at the airport waiting for the flight, Pat Boone was on the loudspeaker singing "Speedy Gonzales", which was quite different from the songs that he usually sang (it was also his last big hit). As we took off from Kai Tak, everyone was praying that we'd get the plane up into the air in time so that we wouldn't end up in the sea, as a few others had done before us. The flight to Singapore, in a RAF Viscount, took only a couple of hours, and we landed at the civilian airport at Paya Lebar. This time, the whole regiment had moved to Singapore and would be stationed in Gillman Barracks, where Dad joined 54 Corps Field Park Squadron. Gillman Barracks was quite near to the city centre, on the road to Pasir Panjang.

SETTLING IN: OUR QUARTER AND SCHOOLS IN SINGAPORE

Our quarter was in a road called Loreng M, which was in the Katong district, just east of Singapore city centre. Our quarter was like a large villa, with an extra-large living room, four big bedrooms and two separate bathrooms. It was without doubt the best quarter we had in all our time in the army, and the garden was half the size of a football pitch. For some reason, I can't remember the name of our amah here. Most of our neighbours were from a Scottish infantry regiment, the 1st Battalion, the Queen's Own Highlanders, and they were a right wild bunch. Near the house was a canal, which stank to high heaven because it was always full of sewage, rubbish and dead animals. Not far from our house was the Muslim area of Geylang, and we could see the mosque's tall minaret from our house. The calls to prayer were blasted out via loudspeakers, and listening to the wailings of the local muezzin four or five times a day was a new experience for us. In those days, a lot of the Singaporeans still lived in kampongs (villages of wooden huts), and the place was nowhere near as clean as it is today. The beach and sea were only about half a mile away, and we went swimming nearly every day after school, either in the sea, in the RAF pool at Changi or in the pool at the Britannia Club, which was near the Raffles Hotel.

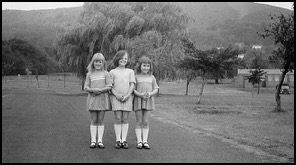

Below: Nicola (left), Teresa (centre) and Tracy (right) in Loreng M.

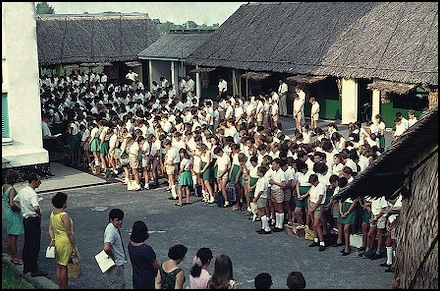

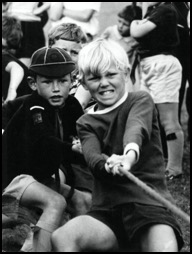

Vicky started school at Alexander Grammar School in Gillman Barracks, whilst Chris and I went to the junior school at Changi and George started at the infants' school there, both of which were near the famous Changi Prison and took about half an hour to get to by bus every day. The school had one large, white building, but most of the classrooms were wooden huts with coconut-leaf roofs. One day in school, we were shown cobras, which someone had caught and put in a large biscuit tin with a sheet of glass over the opening at the top. We could hardly see the snakes because the glass was covered in venom, which the snakes kept spitting at us. At the school sports day, which was held on the RAF Changi sports field, Chris and I were in the tug-of-war team that won the final. We were presented with Dinky toys as prizes and felt quite chuffed about that.

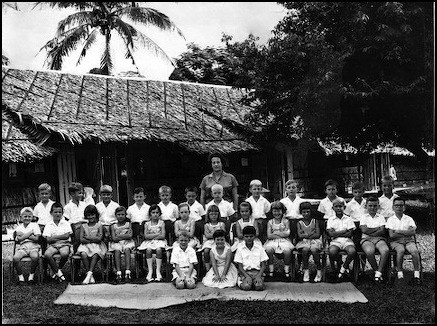

Above: A junior-school class pictured at the school in Changi in 1965.

One day, while we were playing in the road, which was an untarred dirt track, the ice-cream van turned up. Some of the other boys and I jumped on to the back and side of the van to get a ride, but I lost my grip, fell off and my foot landed on a stone. Just at that moment, the back wheel ran over my foot and half-severed my big toe. Having run screaming to my mother with half of my toe hanging off, she quickly grabbed a taxi and rushed me up to the BMH [British military hospital] at Changi. The doctor there said that my injury was so bad, and there was such a high risk of tetanus, that I'd have to stay in hospital. After my toe was sewn back on, I was there for about ten days, and was really glad when I could go home again.

Quite often, we'd go up to the town centre in Katong. They had a large cinema there, and most of the films were shown in English, with Chinese subtitles, so we'd sneak into the cinema and watch them. For the first time, I became aware of a certain Mr Elvis Presley, who made a lot of films during the early 1960s, many of which were shown in the cinema at Katong. By this time, he had already changed his rock 'n' roll style to a more romantic type of music, like "Can’t Help Falling In Love" and "Wooden Heart", and the locals were nuts about him.

One day, I did one of my famous disappearing acts, and this time persuaded Chris to come with me. We decided to go to the Tiger Balm Gardens, which was a park on the other side of the island, and then to take it from there. It took us all day to get there, walking most of the way. When we did, it was dark, and a local Chinese man gave us some food. We told him that we'd left home and that we would spend the night sleeping in the park. Shortly afterwards, a Land Rover full of military police turned up and took us home. One of the locals had rung them up, and when we got home we got a right ear-bashing from Dad before being put to bed.

Chris took his Eleven Plus at Changi at the end of the 1962–63 school year and narrowly failed. After the school holidays, he therefore started school at the old Alexander Secondary Modern School annexe near Kent Ridge Park.

NEW QUARTER, NEW SCHOOL

We left Katong in September 1963 and got a new quarter up in the Pasir Panjang district of Singapore, at number 6, Chwee Chain Road. The reason for the move was apparently that the canal near our quarter was such a health hazard that we weren't allowed to stay there for more than twelve months. In Pasir Panjang, we lived almost next to the sea and went to the local park, which was directly on the seafront, nearly every day after school to swim. (If we weren't swimming here, we’d be up the pool in Gillman Barracks, and I think that I went swimming every single day while we lived in Singapore.) Our new amah was called Muna, but she soon left to have a baby. Her replacement was Ayah, who turned out to be the best amah we ever had: she really treated us like her family, even inviting us to visit her home and family in the kampong, where she fed us Malayan-style jelly.

Another move meant another new school, so I started at the junior school at Pasir Panjang, while George joined me there, but at the infants' school, which was on the large Essex/Sussex military housing estate. (Vicky and Chris did not have to change schools when we moved quarters.) At school, I played football for the first time in my life. The Gurkha boys were the best players, and it was usually the team with the most Gurkha boys that won the knockout cup in the school championships, which took place between the houses.

On Christmas Day, we had our Christmas dinner as usual, although that Christmas was a bit different as Dad decided to give Vicky, Chris and me a glass of sherry with our dinner. It was the first time that I'd tasted alcohol in my life, and I had to admit that I quite liked the sweet, sickly taste.

One of Dad's mates in camp was called Geordie. Football-mad, Geordie was a member of the regimental team that played in the Singapore and Malaya [now Malaysia] league. One day, the squadron was drawn to play against a team stationed in Johor Bahru, in Malaya, in the forces' Asia Cup, so Dad took Chris and me up to Malaya with him in the back of a 3-ton truck to see the match. For the first time in our lives we saw large rubber-tree plantations, and I was amazed by how the trees were all planted in straight rows, like soldiers on parade, no matter which angle you looked at them from. Our team won the match 2–0 and went into the next round of the cup.

At the school sports day, I won the egg-and-spoon race by a mile and felt really pleased with myself. Mum, who was there cheering me on, was chuffed, too. I got a big, round, silver medal, which was held in a plastic container with a big, colourful ribbon tied around it. It was the first time that I'd won an individual medal at sports, but I no longer have it (I never knew what happened to it – it was probably lost on our many travels).

In May 1964, I sat my Eleven Plus, along with the rest of my class, and just failed it. (As I recall, only a couple of kids in my class passed it.) That meant that when I finished junior school, I couldn't go to grammar school, and would have to join Chris at Alexander Secondary Modern School, which would be renamed Bourne School for the new term. Alexander Grammar School was being moved to a new location on the other side of Kent Ridge Park and would be called St John's Comprehensive School, with all of the children in the third year and above being moved to St John's. This meant that Vicky had to move school once again.

In July 1964, the Beatles stopped at Paya Lebar Airport to refuel on their way back to Britain after touring Australia. A lot of the Brits went down to the airport to welcome them, including nearly all the girls in my class. Shortly after that, the film A Hard Day’s Night, which had been made earlier that year, was shown at the Regal Cinema in Gillman Barracks. I went to see it with Vicky and Chris, but couldn’t hear a thing as all the teenage girls screamed their heads off from the moment the film started until it ended. Afterwards, I thought to myself, "Aren't girls funny creatures?"

The school swimming gala was held at the end of term in July 1964. I was made captain of our house team and felt quite proud about that. I was entered into four events and had high hopes of winning some of them. As it turned out, the day turned into a personal disaster for me. During the gala, our team had done quite well, and were neck and neck with another house in the race for the team cup, although I had finished only second in my first three events. In the last race, which was the medley relay, we only needed to finish second to take the house cup. I was the last swimmer in my team, doing the crawl length. During the race, I became so excited that I dived in before the previous swimmer had touched the wall, so our team was disqualified. The disqualification cost us the cup, and I was bitterly disappointed with myself for having let the team down, despite having won three individual certificates.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART VIII

The autumn of 1964 found the Rutledge family in Singapore, where they had been living since 1962 (see Part VII, above). Prior to that, thanks to Leslie's father’s career in the Royal Engineers, they had twice made their home in Hong Kong, as well as in (West) Germany, England and Trieste. Leslie now continues his story by describing his new school. (See below for parts IX to XI, and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood.)

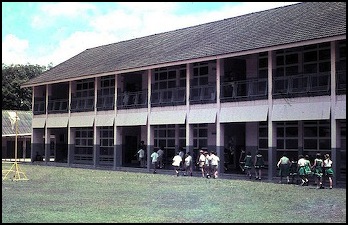

'I started senior school at the beginning of September 1964, and joined Chris at Bourne School, a secondary modern in Gillman Barracks. Bourne School was similar to my junior school at Changi, in that the main building was whitewashed concrete, while the classrooms were wooden huts with coconut-leaf roofs. The school was actually split into two parts, which were about a mile apart. I was in the part that had the famous 121 steps up the hill, a stone's throw away from the swimming pool at Gillman Barracks.

Above: An assembly at Bourne School.

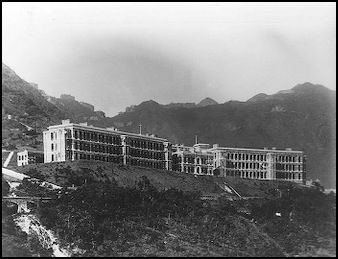

Below: Bourne School, featuring the famous 121 steps and Gillman Barracks.

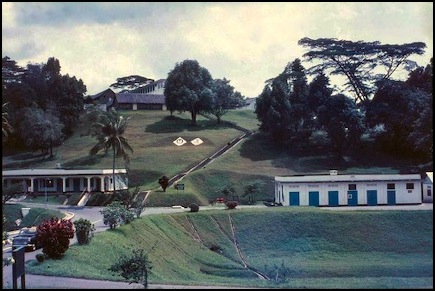

Below: St John's Comprehensive School, which Vicky attended.

After our football trip to Malaya [now Malaysia], Dad would quite often take Chris and me with him to matches to watch the regimental football team. The team was quite good, and reached the army cup final in the Asia zone, which they lost, 1–3 as I recall. After the matches, there were always a few urns available, with tea, coffee, Tiger beer and shandy for the players and supporters. Chris and I would look at Dad drinking his beer with hungry eyes, and he once let us help ourselves to a glass of shandy.

One day, the families in the street decided to have a fancy-dress party. Mum dressed me up as a girl, and I went and stood with the boys. One of the blokes, who was running it, said to me, "The girls are over there, Miss", and we all have a good laugh when I told him that I was a boy. I won first prize, and felt quite pleased with myself. One night, Mum and Dad took us to the Cathay Cinema in Singapore city centre, which was a lot larger and posher than the Regal in Gillman Barracks, having enough room for a few hundred people, and being set out on about four levels. It was the most modern cinema in Singapore, and the rows of plush seats were really steep, with the heads of the people in the next row down at our feet. We sat near the back, at the highest level, and I remember spending more time looking down at the hundreds of heads than watching the film (In Search of the Castaways, starring Maurice Chevalier and Hayley Mills).

For about the last year that we lived in Singapore, we hired a telly. It was the first time that we'd had one of our own, and we wouldn't have one again until we moved to Malvern Wells, in Worcestershire, in 1968. Most of the programmes we watched were American, like "77 Sunset Strip" or "Bat Masterson". We'd quite often watch the news delivered in an Indian language [possibly Tamil], and soon picked up a few phrases (not that they ever came in handy), like Vanicum sadihum sadichurum, which meant "Good evening, here is the news".

MALAYSIA AND BORNEO

During the time that we lived in Singapore, the colony was going through a lot of political upheaval. When we arrived, it was still a British colony, but in 1963, it decided to join the newly founded Federation of Malaysia. At the same time, Indonesia started what was to become officially known as the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, which was also called the "secret war" as nobody really knew what was going on in the jungles of Borneo until it was all over. All of the British military in the area got involved in the war either directly, by being sent to Borneo, or indirectly, in a supporting role from Singapore, Malaya and Hong Kong. During the war, Singapore suffered more upheaval when race riots broke out in 1964 between Muslims and the Chinese in Geylang, with a lot of people being killed and injured and large parts of the island being placed under curfew. But we'd moved up to Pasir Panjang by that time, so we were well away from the riot areas. In August 1964, Indonesia raised the stakes when it started to attack Malaya directly, first with an amphibious assault and later with a series of paratrooper attacks in the state of Johor Bahru, most of which were dealt with quite quickly. I remember that once, when Indonesian paratroops landed in Labis, in Johor Bahru, even Singapore was put under a two-day curfew until they were all rounded up.

At the beginning of October 1964, Dad came home and told us that he was going to Borneo, which surprised us as we were only three months off leaving Singapore and a tour of active duty was normally for four months. As it turned out, he was only sent there as a makeshift replacement for someone having a personal crisis, but it was up in the air when he would return. He flew out to the island of Labuan and was then transported to Brunei, where he served in a Royal Engineer resources troop. (Being a storeman-tech, he was well away from any fighting, but still got a campaign medal out of it, the only one he received while in the army.) In the event, he only stayed over in Brunei for seven weeks – after all, we were leaving soon and needed someone to pack up our crates. So Dad came back from Borneo in mid-December, and we were all happy to see him again, especially Mum, as we were now only a few weeks away from leaving for our next posting. He brought us all presents, and I got a pair of real football boots – my first pair. I was starting to develop into quite a good little footballer and played a lot when we weren't swimming.

Just after Dad got back from Borneo, he treated us to a day out in Malaya and got his mate, Geordie Laker, to do the driving. (Mum and Dad treated Geordie, who had also been posted back to Blighty, almost like a son.) First, we went to a place called Kota Tinggi, which was somewhere in the jungle, and which had a lake and a waterfall coming out of the mountain; nearby was a large tin mine, tin being abundant in Malaya. We stayed there for a couple of hours before Geordie decided to take us to the sea, to a place called Jason Bay. After about an hour's drive through dense jungle, we came upon the most breathtaking beach – it was about as near as I've ever been to paradise. There were a lot of beaches in Singapore, but they all had a background of built-up areas, while this place had no sign of life anywhere. The waves were quite high, so we found an old coconut tree lying near the beach and, after a struggle, got it into the water and started surfing on it, which was great fun. We had brought enough grub to feed an army of soldiers, never mind a family, and had a picnic, which seemed to last for hours. Eventually, it started getting dark and we had to make our way home. Driving back through the jungle in the dark, with all the various noises coming out of the thicket, was quite eerie. If I've ever had a day in my life that I never wanted to end, it was that one. About a week later, Geordie left for home and we never saw him again. That was one of the saddest things about army life: when you had to say goodbye to a dear friend, knowing that you'd probably never see him or her again.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART IX

At the start of 1965, when Leslie Rutledge picks up the thread of his tale in this, Part IX of his army-child story (see above for previous instalments, below for parts X and XI, and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood), his father, who was in the Royal Engineers, had just been posted from Singapore to (West) Germany. The town of Willich would provide the Rutledge family's third German home, but they would be staying in Blackpool for a few weeks before arriving there.

'In January 1965, the news came through on the radio that Winston Churchill had died, and that the whole of the UK was in mourning. Shortly before that, Dad had learnt that he'd been posted back to Germany, and that our next stop on life's long road would be the large Royal Engineer stores depot in Willich, which lay between Krefeld and Mönchengladbach. The family would have to stay at a boarding house in Blackpool until we got a quarter in Germany, however.

In February 1965, the minibus arrived to take us to the Seven Stories Hotel in Singapore's city centre. All of the British families flying out of Singapore spent their last night there. The hotel was not appropriately named as it actually had nine floors (on its completion in 1953, it was the tallest building in the city centre; as time passed, it became dwarfed by the skyscrapers that went up around it, and it was demolished in 2008). The next day, we were transported to the airport at Paya Lebar. Our relationship with Asia was over for now: Mum and Dad would never return (it would take me another twenty-four years before I went back), and I'm sure that we were all sad as we flew out of Singapore. During the flight back to England, we were only supposed to stop at Bombay [now Mumbai] and Istanbul, but shortly after take-off from Bombay, a bad storm brewed up, and the flight was redirected to Karachi, in Pakistan, for safety reasons, where we were grounded for several hours until the storm had passed. We then flew on to Istanbul, where we landed in the middle of the night. After about a two-hour stop, we flew on home to England and landed at Prestwick, in Manchester, catching a train up to Blackpool from there.

"I NEVER LIKED CIVVY SCHOOLS"

Blackpool is the north's largest seaside resort, being mainly popular with the northern working classes, and being full of entertainment arcades, fairs and so on. In Blackpool, we lived in a hotel just behind the main street (which was known as the Golden Mile), near the central pier in Bairstow Street. The hotel was a bit of a dump, especially the view out of the back window. It was like an old Victorian house, with about six floors staggered on different levels. We had three double bedrooms, as I recall. There was a TV room for the residents, which caused a few rows over who wanted to watch what, and we had our first taste of "Coronation Street" here, which was broadcast in black and white at that time and featured Ena Sharples. The toilets and bathroom were on the landing, and were for general use. In our spare time after school or at the weekends, we'd be playing football on the beach, or would be in and out of the arcades.

Vicky attended Blackpool Collegiate School for Girls, while Chris and I went to the nearest secondary modern school, which was called Stanley and was situated near a large park of the same name. George went to Revoe Community Primary School just around the corner. I must admit that I never liked civvy schools. They had a distinct lack of discipline compared with army schools, and the social status of the pupils was more apparent. Army schools also seemed to have the better teachers. In civvy street, most of the well-off kids went to grammar school anyway, but in a school like Stanley, some of the kids came from very deprived homes, and it showed in their behaviour and dress. Most of the wooden school desks had more carvings in them than a Chinese ornamental chest. In army schools, by contrast, all of the fathers were employed, and a strict code of dress and discipline was adhered to – or else!

During our stay in Blackpool, I became more aware of many of the big pop groups around at the time. The Beatles had become famous so quickly that they were well known in Singapore. Other groups, like the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, the Hollies, Manfred Mann and Herman's Hermits may have been well known in England, but no one had heard of them in the Far East. The Kinks brought out a record called "Dead End Street", which always reminds me of our stay in Bairstow Street.

Just before we left Blackpool, I saw my first ever-professional football match live. The visitors were Chelsea, and on the day of the match there was a big stink in the newspapers because most of the Chelsea team had sneaked out of the hotel using the fire-escape stairs and had spent half the night boozing downtown. Tommy Docherty, Chelsea's manager at the time, sent some of the players home, including Terry Venables, who would later become England's manager (George and I would bump into him in Paris in 1995). Chelsea sold several players, including Venables, shortly after the incident. On the night of the match, Blackpool won a good game 3–2. The young Alan Ball was playing for Blackpool, and a year later would be England's youngest player when they won the World Cup.

WILLICH, RHEINDAHLEN AND WALDNIEL HOSTERT

After staying in Blackpool for seven weeks, we received news that our quarters were ready in Germany – because of the size of our family, and because there were no four-bedroom quarters in Willich, we would be moving into two flats to accommodate us all. In April 1965, we caught the train to Manchester and then flew out of Prestwick to Düsseldorf. On our arrival, we were greeted by the driver of a minibus, who transported us to Willich, where we moved into our new double flat in Friedhof Straße.

Dad's new unit was 40 Advanced Engineers Stores Regiment, which was stationed at Kitchener Barracks in Willich. Vicky started school at Queen's School, Rheindahlen, while Chris and I went to school at Kent School, a secondary modern located in an old disused German hospital at Waldniel Hostert, near Rheindahlen. It was my ninth different school in just over four years, but I suppose that was the life of a pads' brat – no wonder we were called "rootless wandering nomads". This time, I would stay put for three years, which would be my longest attendance at any one school. George went to the infants' school at Borkum, in Krefeld.

Above: George in 1965 (left); Mum and Dad in 1966 (right).

There was a rumour going around that my new school had been used during the war for experimenting on Jews. There seemed to be some evidence to support this theory as an old Jewish graveyard was discovered in the woods in the hospital grounds. Who knows if there was any truth in the rumour, but it certainly made the place a bit creepy, especially as almost half of the complex was empty and out of bounds to us school kids. (That didn't stop us exploring the out-of-bounds areas during our lunch hour, though, which cost me six of the best on more than one occasion.) But if the Nazis had committed any atrocities here, they'd certainly left no traces. Later on in life, I read that euthanasia experiments on children with handicaps had been carried out at Waldniel Hostert during the war years.'

Leslie Rutledge (b.1953).

PERSONAL STORY: LIFE AS AN ARMY CHILD, 1950–70,

PART X

Having already lived in Trieste, England, (West) Germany, Hong Kong and Singapore, the mid-1960s found the Rutledge family back in Germany, settling into their new home in Willich, to which their Royal Engineer father had been posted from Singapore in 1965. (See above to read about their previous experiences; below for Part XI of Leslie Rutledge's account; and click here for his personal observations on an army childhood.) Read on to find out what life was like for a British army family stationed in Willich at that time, and how their German neighbours reacted when England beat West Germany to win football's World Cup in 1966.

'Because Willich was only a small military town, we didn't have our own NAAFI or Toc H, and a YMCA van would visit our quarters' area once a week. Mum would buy us all a comic each: The Beano, Dandy, Victor and Eagle for the boys, and Bunty, Judy, June and Jackie for the girls. Dad got The Weekend magazine and Titbits, which was full of bikini-clad beauties, and Mum got herself Woman and Woman's Own. One of the cartoon stories in The Beano was called "Tom, Dick and Sally", about siblings who lived with their father, who they called "Pops". We started calling Dad "Pops", too, and the nickname stuck. Shortly after that, Mum was given the nickname Mutti [German for "Mum"] as we were living in Germany, and that nickname stuck as well. Twice a week, a bus was laid on to go to the NAAFI shop, and also to the cinema in Bradbury Barracks in Krefeld.

FOOTBALL IN GERMANY

After school, we'd spend quite a lot of time playing football outside our block of flats, and sometimes even in it (down in the cellar when it rained). Sometimes, we'd play on the large fields just behind our flats, where the locals held their Schützenfest [a fair featuring shooting competitions] every year. A lot of the local German kids also played football there, and we had some really good matches against them, sometimes also mixing the nationalities and playing each other in mixed teams. I got particularly friendly with one boy called Otto, who looked just like the stereotypical German, with his short-cropped blond hair and traditional leather shorts. Eventually, the German boys asked us to join the local German football club, and I, Ken Napier and the three eldest Cox brothers did so. During the two years that I played for the "C" (youth) team, we had only limited success, finishing fifth and seventh in the league, as I recall, but team morale was quite good, and the Germans accepted us with no problems. One day, we were playing away in Krefeld to Bayer Uerdingen's youth team, which was top of the league. (The first team played in a professional capacity in the German regional league, and would later play for about six years in the Bundesliga and win the German cup.) During the match, I scored a goal from my own half, which was the first time that I'd managed such a feat (I'd accomplish it three more times before I hung up my boots). But we lost the match 2–5, and Uerdingen went on to win the league, as they did every year. During that season, we also played another match away in Krefeld, to a team called Preußen Krefeld, whose first team was also semi-professional. On the Sunday that we played there, the first team was due to play as soon as our game finished. We lost the game 2–0, and by the time that the final whistle was blown, a crowd of about 3,000 spectators had gathered, which was the largest audience I ever played in front of (we were used to a crowd of about 50 mums and dads). During the two years that I played in Willich, I scored about ten goals in about forty matches, which I felt, was not a lot.

In July 1966, the football World Cup started in England, and hopes were high that England would win it, although they’d never really done well in the competition so far, and had never even reached the semi-finals before. We didn't have a telly, but the Jones's, who lived in the block next to us, had one and let us in to watch the matches on it. As England progressed through the competition, excitement reached fever pitch, especially when they got to the final and we knew that their opponents would be West Germany. On the housing estate where we lived, there were only about half a dozen families with a telly, and everyone wanted to watch the final live. We'd booked our usual seats in the Jones's house, but this time the place was packed to the rafters, with everyman and his dog there. The beer was flowing, but only for the adults, and the atmosphere was electric. After a thrilling match, which England won, we all went mad and rushed out on to the street cheering and shouting. The place reminded me of the eye of the hurricane in Hong Kong as an eerie silence fell over the town; there was not a German in sight – it seemed that they had taken defeat pretty badly.

GROWING UP

In the summer of 1966, Vicky left school and started work in camp as a secretary. I think that this was something that she later regretted because she certainly had the brains to go to university. I think that, like a lot of girls, she had just reached that age when having fun and going out with boys was more important than school. Shortly after that, she started dating one of the soldiers in camp, who she would go on to marry in 1968. After the summer holidays, Nicola started infants' school in Krefeld and travelled up there with George on the bus every day.

I tried my first cigarette that summer. Like most young teenagers, I was intrigued as to why so many grown-ups smoked, and both of my parents were smokers. I thought to myself, "I will have to try this wonderful method of medication", and one day I got my chance. Several of the older kids smoked on the school bus, and one of the girls offered me a cigarette to try. After I'd inhaled the smoke, I couldn't stop coughing for about ten minutes, and thought to myself, "Where is the pleasure in this?" One of the other girls on the bus, who was a non-smoker, took the cigarette off me and inhaled it four or five times through a handkerchief. Then she unfolded it and showed me the black, sticky patches of tar on the handkerchief. "Is that what you want to put in your lungs for the rest of your life?" she asked me. I decided that I didn't, and never smoked again.